The U.S. should be prepared for massive changes in the next few years in the way physicians are trained, experts said here Thursday.

Change will have to start with inter professional education, George Thibault, MD, president of the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation in New York, said at an event sponsored by Health Affairs to promote its theme issue on medical education. “We know all health professionals are going to work together in formal and informal teams, yet we educate them separately and then are surprised when they don’t work together well.” Instead, professionals should be educated together so they are prepared to work together as teams, he said.

In addition, a new model of clinical education is needed, Thibault continued. “The [current] model is very fragmented and still too hospital-based to take care of a population with chronic illnesses who are largely outside the hospital. The model needs to be more longitudinal and community-based.”

Then there is the content of the curriculum. “Since [the Flexner report], biological sciences have been the basis for medical education,” he noted. “We need to add social sciences, systems management, economics, and medical professionalism.”

Thibault also suggested that medical schools move away from time-based education and toward education based on development of competencies, “so learners move through as they are ready to move through. We cannot continue to have a locked-up approach determined by everybody doing the same thing or determined by just time and place. This can lead to a more efficient system … and to professionals who are specifically prepared for the careers they’re going to take on.”

Several speakers lamented the lack of medical students willing to go into primary care. “Part of that is the culture of medical school — what’s conveyed to students plays a major role,” said Uwe Reinhardt of Princeton University in New Jersey.

“You come home and you say, ‘I’m a pediatrician,’ or you say you’re like Sanjay Gupta — a neurosurgeon. What gets you the date?” he said.

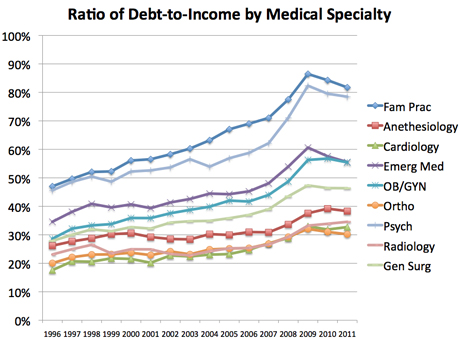

Although people often point to medical education debt as a barrier to pursuing the lesser-paid primary care specialties rather than the more well-paid specialties, Reinhardt disagreed that it’s a major problem. “Look at medical school indebtedness — on average it’s about $220,000,” he said. “I always tell physicians who bellyache, ‘you know that guy who just opened a restaurant — what do you think they pay on a mortgage?’ It’s probably close to your [loan], and somehow they make do.”

“Debt is a nuisance, but not prohibitive,” he added, noting that the Association of American Medical Colleges is trumpeting record medical school enrollment despite students’ debt problems.

For the primary care situation to change, “we need accountability,” said David Goodman, MD, of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in New Hampshire and a co-principal investigator of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. “The best way is with public guidance leading to peer review that leads to public funding,” with priorities that are set annually. “That might [include] increase in primary care [residency] funding — putting a thumb on the scale allows being a priority.”

Goodman proposed a scheme in which each year, 10% of physician training programs would need to reapply for their funding. Programs that are reapplying would be competing with other established programs as well as new residency programs. Applications would be peer-reviewed, and successful applicants would get an interim review to make sure they were on track.

Under such a system — which would mean that each program would be reviewed once per decade — meritorious training programs would be able to expand, while weaker programs would lose 10% to 15% of their funding. And because the awards would be made every year, it would give the system “the ability to change priorities with each succeeding year, over time,” he said. “Sure, we’ll make mistakes, but they’ll be smaller mistakes.”

Audience members also heard from Reps. Aaron Schock (R-Ill.) and Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.)who are co-sponsoring the “Training Tomorrow’s Doctors Today Act,” a bill that would increase the number of graduate medical education (GME) slots by 15,000 over a 5-year period. “This is an issue that’s uniting [Republicans and Democrats] on Capitol Hill,” Shock said.

Both Schock and Schwartz also expressed support for legislation that would repeal and then replace Medicare’s much-maligned sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula for physician reimbursement. Schock noted that one reason the House Energy and Commerce Committee was able to get unanimous support among its committee members for its SGR repeal proposal, which would cost an estimated $179 billion, was that “they didn’t say how they’re going to pay for it.”

Rep. Dave Camp (R-Mich.), chair of the House Ways and Means Committee — which is charged with coming up with ways to pay for legislation such as an SGR fix — has been briefing committee members on possible “pay-fors,” said Schock, who is a member of the committee. “So stay tuned” to see what happens, he added.

Schwartz said she hopes that GME reform may eventually be included in an SGR fix bill should one be passed. “When we do something about the SGR, there might be a moment when we could slip this [GME] legislation into our discussion,” she said.

Source: Med Page today

Nevada’s university leaders have signed a partnership agreement to begin establishing a new M.D.-granting medical school in Southern Nevada.

Nevada’s university leaders have signed a partnership agreement to begin establishing a new M.D.-granting medical school in Southern Nevada.

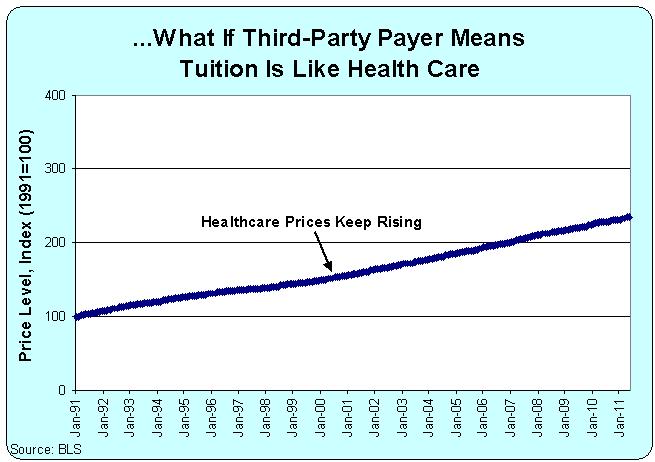

“In the case of medical education, students buy their education from medical schools and resell that education in the form of services to patients. Medical education can remain expensive only so long as there are patients, insurers, and employers who are willing to pay high prices for health care. But if prices for physician services decline, then the cost of medical education will have to decline too, or people won’t be willing to pay for medical school in the first place,” Asch says.

“In the case of medical education, students buy their education from medical schools and resell that education in the form of services to patients. Medical education can remain expensive only so long as there are patients, insurers, and employers who are willing to pay high prices for health care. But if prices for physician services decline, then the cost of medical education will have to decline too, or people won’t be willing to pay for medical school in the first place,” Asch says. Medical school applications and enrollment reached record highs this year as organized medicine’s cries for more funding for residency slots continued with little response from Congress.

Medical school applications and enrollment reached record highs this year as organized medicine’s cries for more funding for residency slots continued with little response from Congress.