New York state received 20 percent of all Medicare’s graduate medical education (GME) funding while 29 states, including places struggling with a severe shortage of physicians, got less than 1 percent, according to a report published today by researchers at the George Washington (GW) University School of Public Health and Health Services (SPHHS).

New York suffers from no lack of physicians yet in 2010 the state received $2 billion in federal GME funding according to the study, which appears in the November issue of Health Affairs. At the same time, the researchers found that many states struggling with severe physician shortages received a fraction of that funding: For example, Florida received one tenth the GME funding ($268 million) and Mississippi, the state with the lowest ratio of doctors to patients in the country, received just $22 million in these federal payments.

“Such imbalances play out across the country and can affect access to health care,” said lead author Fitzhugh Mullan, MD, the Murdock Head Professor of Medicine and Health Policy, a joint position at SPHHS and the GW School of Medicine and Health Sciences. “Due to the rigid formula that governs the GME system, a disproportionate share of this federal investment in the physician workforce goes to certain states mostly in the Northeast. Unless the GME payment system is reformed, the skewed payments will continue to promote an imbalance in physician availability across the country.”

Other authors of the study include Candice Chen, MD, MPH, assistant professor of health policy and pediatrics and Erika Steinmetz, MBA, senior research scientist at the SPHHS Department of Health Policy.

The study adds to the evidence suggesting that the current system of allocating graduate medical education or GME money is based on an inflexible and outdated method, one that contributes to large imbalances in payments and a growing shortfall of physicians in some areas of the country. Since its start, the Medicare GME program has paid teaching hospitals to provide residency training for young physicians. In 2010, those teaching facilities received $10 billion in GME payments, an amount that represents the nation’s single largest public investment in the health workforce.

To find out how that $10 billion was distributed, the researchers analyzed the 2010 Medicare cost reports that list federal GME payments to teaching hospitals all over the country. The team found a disproportionate amount of Medicare GME dollars flowing to Northeastern states such as New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In fact, the study shows that in these three states Medicare supports twice as many medical residents per person as the national average. And New York alone has more residents than 31 other states combined.

“Teaching hospitals in the Northeastern United States have a long history of large residency training programs, which capture a large share of GME funding,” Mullan said. “But these states also have the highest physician-to-population ratios. They are not doctor shortage states.”

While some residents move elsewhere after training, the majority of newly minted physicians set up a practice near where they were trained. Therefore, it is important that states with rural and growing populations receive appropriate support for starting and maintaining residency programs, Mullan said.

The study shows that many other parts of the country lose out when it comes to Medicare GME funding. Many Southern and Western states — which already face shortfalls in their physician workforce — such as Montana, Idaho, Arkansas, Wyoming, Florida and even California do not do well in terms of Medicare GME funding under the current system, according to the authors.

The researchers also found:

Large state-level differences in the number of Medicare-funded medical residents even when the density of the population is taken into account. For example, New York again is at the top of all the states with 77 Medicare-funded medical residents per 100,000 people while California has 19, Florida 14, and Arkansas has just 3.

Medicare GME payments have not kept pace with factors such as rapidly growing populations in Southern and Western United States. For example, Florida, Texas and California have rapidly growing populations yet they received substantially less GME funding in 2010.

Medicare’s current GME formula pays very different amounts to train medical residents depending on the state. For example, the federal government pays Louisiana $64,000 per year to train each medical resident but gives Connecticut $155,000 for the same job

- The findings from this paper document a substantial imbalance in GME payments, one that has been frozen in place since 1997 when Congress passed a law that capped the number of residency positions at each hospital. Under the 1997 law, teaching hospitals can train any number of physicians but Medicare pays for the training only up to the allocated cap, the authors point out.

- The end result of the cap and other inflexible attributes of the current GME system is a system that gives teaching hospitals in certain states with large numbers of practicing physicians big incentives to train more residents while shortchanging many smaller and rural states.

Ways to fix the problem include revisiting the GME payment formula and devising one that distributes GME funding so as to stimulate the growth of residency training in parts of the country that are chronically underserved or are growing rapidly. In addition, the authors say the GME funding system needs an oversight body that would look now and in the future at the distribution of GME dollars and make decisions about the best places to steer funding so that the federal government is making the wisest investment in the physician workforce.

Source: Science Daily

Nevada’s university leaders have signed a partnership agreement to begin establishing a new M.D.-granting medical school in Southern Nevada.

Nevada’s university leaders have signed a partnership agreement to begin establishing a new M.D.-granting medical school in Southern Nevada.

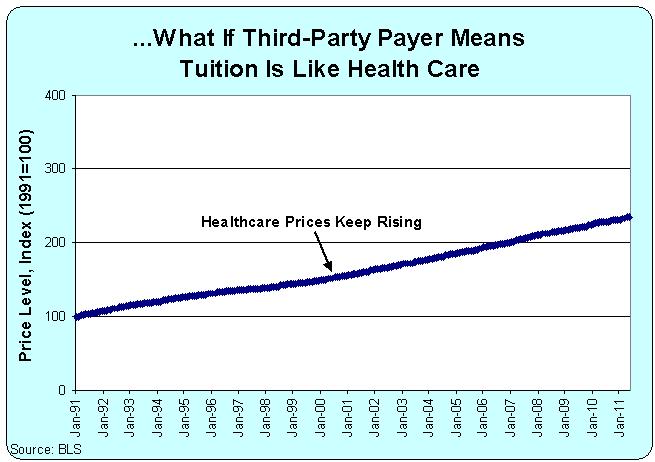

“In the case of medical education, students buy their education from medical schools and resell that education in the form of services to patients. Medical education can remain expensive only so long as there are patients, insurers, and employers who are willing to pay high prices for health care. But if prices for physician services decline, then the cost of medical education will have to decline too, or people won’t be willing to pay for medical school in the first place,” Asch says.

“In the case of medical education, students buy their education from medical schools and resell that education in the form of services to patients. Medical education can remain expensive only so long as there are patients, insurers, and employers who are willing to pay high prices for health care. But if prices for physician services decline, then the cost of medical education will have to decline too, or people won’t be willing to pay for medical school in the first place,” Asch says. Medical school applications and enrollment reached record highs this year as organized medicine’s cries for more funding for residency slots continued with little response from Congress.

Medical school applications and enrollment reached record highs this year as organized medicine’s cries for more funding for residency slots continued with little response from Congress. Each year hundreds of medical students think they have contracted the exact diseases they are studying. But they haven’t.

Each year hundreds of medical students think they have contracted the exact diseases they are studying. But they haven’t.